Why did the Scots leave for East Jersey?

Exploring their motivations

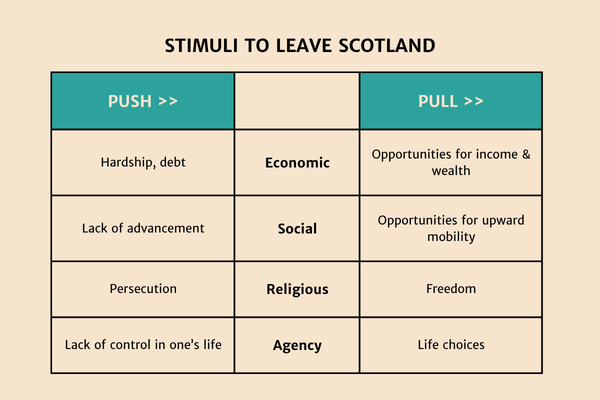

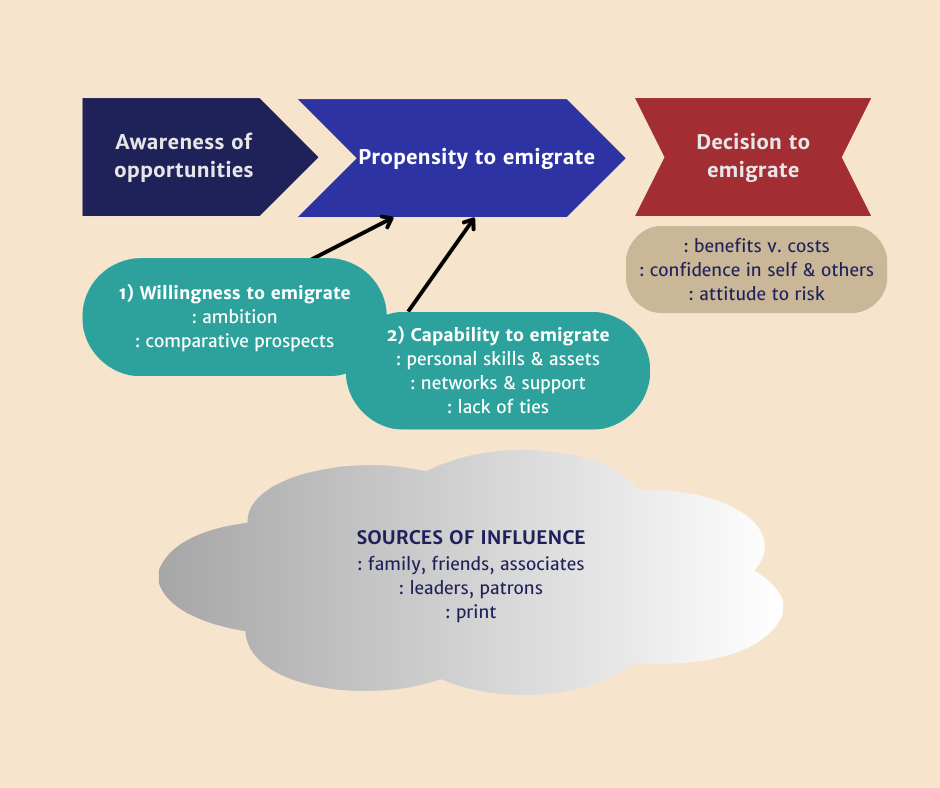

The reasons why the Scots left for East Jersey were many and often overlapped: family ties, religious convictions, economic pressures, social ambition and the promise of land and opportunity in a new world. Only some of the Covenanters travelled freely while others were encouraged to leave or banished.

The factors were both extrinsic, notably where the emigrants weighed up their prospects for a better life against staying at home, and intrinsic, such as their spirit, self-confidence and positive attitude to risk.

Full details can be found in my dissertation, Scots Emigrants to East New Jersey, 1682-1702: Motivations and Outcomes, University of Glasgow, 2025

Read or download ‘Scots Emigrants to East New Jersey’ here

Factors at play in decisions to emigrate

How did they become aware of the opportunities?

Family influence

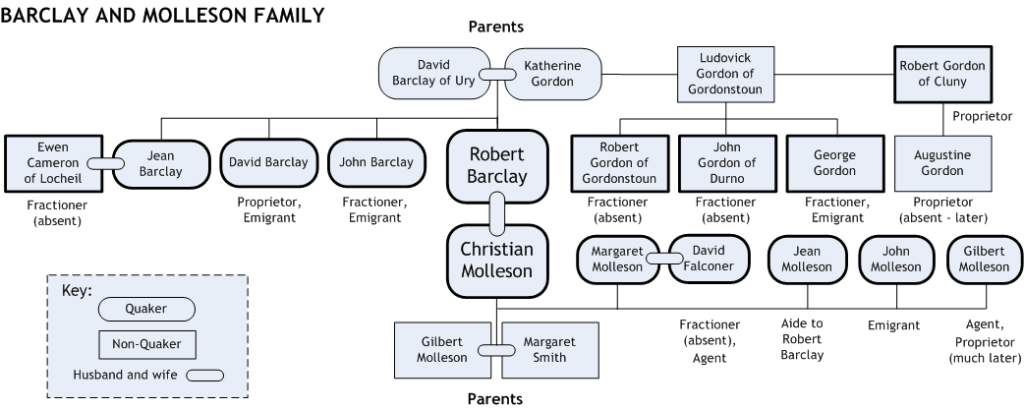

Amongst the leaders of the venture, a number came from families with a long history of transatlantic interest, stretching back to earlier colonial efforts in the 1620s. Six of the early investors were direct descendants of Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun, the first Baronet of Nova Scotia, while six more had close family connections with other baronets who all invested in this earlier enterprise. In the first group were Robert Barclay of Ury, his younger brother David and their uncle Robert Gordon of Cluny, and in the second, Robert and Thomas Fullarton from Kinnaber in Angus and Charles and Thomas Gordon from Pitlurg in Banffshire. Kinship wasn’t just about inspiration; it also facilitated involvement in the colonial venture, as a source of advice, investment, and mutual support.

In several cases family involvement in the East Jersey project became a family enterprise: notably that of Robert Barclay, son of Colonel David Barclay of Ury, and his wife, Christian Molleson. In addition to Robert himself, some 10 close kin invested in East Jersey, of whom four emigrated (see diagram below). Several acted as emigration agents and Christian’s sister Jean was Robert’s administrator.

Promotional efforts

Many Scots learned of the East Jersey opportunities by word of mouth through not only through their close kin but also others within their wider circle of acquaintances: fellow workers on the land or craftspeople, local lairds, merchants and traders. Letters home from the first settlers in 1683 and 1684 were also published in promotional tracts – like modern sales prospectuses – to support the arguments for emigration. Between 1683 and 1685, six of these were published including one aimed specifically at tradesmen and farm servants.

Faith networks

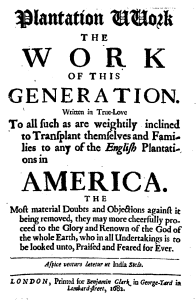

Quakers notably formed a tight-knit community. Their shared experience of persecution made them reliant on one another for information and support, leading to widespread awareness of the East Jersey project. For many religious conviction was entwined with commercial ambition. Publications like Thomas Loddington’s Plantation Work exhorted the development of both an ‘inner plantation’, nurturing a healthy spiritual life and community, and an ‘outer plantation’ through work and commerce, creating property and opportunities for the next generation.

Quaker emigrants included gardeners, John Reid and John Hamton, appointed as overseers of the first settlement in 1683, tenant farmer William Ridford, laird John Laing of Craigforthie, Doctor William Robertson and their families. George Keith followed in 1684 when appointed as East Jersey surveyor.

Their faith network could have been a factor for the more determined of the Covenanters, but in contrast they were suspicious of the motivations of those promoting the venture.

Business and social networks

This was a fertile time in merchant networks for exploring and developing new business ideas, of which colonial ventures were but one strand. Some pursued novel manufacturing ventures such as the New Mills textile factory in Haddington, amongst whom several were active in plans for East Jersey such as Robert Blackwood and John Drummond of Newton.

There was common envy of England’s burgeoning transoceanic trade and dismay over the constraints imposed on Scottish trade by England’s Navigation Acts, accompanied by enterprising ways of circumventing these. The development of Scots colonies was seen as a solution.

Many of the prominent Scots Quakers were merchants and had close links to their London counterparts already engaged in transatlantic commerce. Gawen Lawrie was one involved from the outset in plans for the disposal of a large amount of land in New Jersey as a trustee of Edward Byllynge who was threatened with bankruptcy.

Freemasonry connected some of the protagonists, especially those who were ‘speculative’ (ie, not working) freemasons. This was a new phenomenon, part of early Enlightenment culture centred around Edinburgh’s court of James, Duke of York before he became king.

Leadership figures

Leaders within communities exercised significant influence in promoting emigration, stemming from their reputation, formal position of authority or personal attributes.

The most influential Scot was the noted Quaker theologian, Robert Barclay. He was an able to operate effectively in different worlds, in the family estate in Kincardineshire, in Quaker meetings, in merchant dealings and in the court politics of Edinburgh and London. He was well-respected and had great powers of persuasion. He was the driving force behind the early emigrant voyages and accepted the role of East Jersey Governor, though as non-resident.

Lord Neill Campbell was a prominent member of Clan Campbell and brother to the rebel Earl of Argyll, who partnered Edinburgh merchant Robert Blackwood to fund the voyage of the America Merchant in 1685. As a high-status Highland landowner, he could draw on traditional allegiance within the clan and act as a figurehead in attracting other emigrants.

George Scot of Pitlochie was a committed Covenanter with a stubborn streak, leading him to incurring fines and imprisonment, including on the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth. His lengthy promotional tract, The Model of the Government of the Province of East-New-Jersey in America; and Encouragements for Such as Designs to Be Concerned There, Etc (1685) comprehensively set out the case for Scots to emigrate, particularly Presbyterians. He exhaustively rebutted opposing arguments, of which there were many. He had some success but failed to convince many Covenanters who wanted to stay and resist what they saw as a tyrannical royal regime.

Why did the Scots leave?

Putting to one side the transported prisoners…

Economic and social advancement

For most, emigration was about economic betterment. This could reflect the draw of opportunity or the push of adverse personal or family finances. A new world could also offered prospects of moving up the social ladder, in contrast to rigid hierarchies in Scotland.

- Debt: minor nobles and lairds often faced mounting debts from inheritance, lifestyle, or fines for religious dissent. Emigration offered a fresh start for the likes of David Toscheoch of Monzievaird whose family had been burdened by the debts of his grandfather.

- Primogeniture: Younger sons stood little chance of inheriting land at home. East Jersey gave them the chance to own their own property. This was the case for the likes of the Gordon brothers of Pitlurg, the Fullartons of Kinnaber and James Dundas from the Arniston family of landowners and judges.

- Merchants: Many saw potential for new markets and a path to an estate and the title and status associated with it. This was the case for Gawen Drummond from Prestonpans and his nephew Robert.

- Farm servants and tradespeople: Indentured service offered a route to a better life: after a few years of work, landownership was within reach. John Cockburn writing to fellow mason George Fae in Kelso strongly advocated the opportunities on offer:

“It is a very pleasant Countrey and good for all Tradsmen; you was angry with me for coming away but I repent nothing of it myself, for I have abundance of imployment… Any who hath a mind to come here will get good wages; these will do far better than in Scotland”.

Religious motivation

Freedom of religion mattered for some. For Quakers there was the chance to live out their ideals in peace, while some Presbyterians responded as free emigrants to George Scot’s call to escape persecution. The latter included members of his wife Margaret Rigg’s family and merchants James Armour from Glasgow and William Ged from Burntisland, the latter with his family.

Personal drive

There was also a strong current of individual ambition and enterprise. Letters from emigrants – such as Cockburn’s above – show pride in defying sceptics and critics back home. These were people willing to take risks, leaving behind all they knew. Most were in their twenties and thirties, determined to seize the opportunity.

Who could emigrate?

Participation in colonial ventures was expensive. Some investors such as John Campbell from the Duncrosk family of Weem in Perthshire sold land while others relied on credit to fund their emigration.

Others could not afford to finance their emigration themselves, lacking the costs of their passage (£5/adult, £2 10s/child) and those associated with early settlement. Indentured servitude was their opportunity, where they would have their fares paid and clothing and victual provided in return for usually four years’ service, at the end of which they would have a grant of land, typically 30 acres. Examples included John Oliphant and Janet Gilchrist from Pencaitland in East Lothian who were indentured to Quaker John Hancock in 1685. Their two daughters, however, were under contract until they reached 21.

Family connections and business contacts could also be key to making the move possible. Emigration was not an option for those with no money or relevant skills to offer.

In a nutshell

The motivations behind the East Jersey migration were complex:

- For the majority, it was economic betterment.

- Some sought their own land, for their independence and a sign of social advancement.

- Religious freedom mattered for a minority, a factor mainly for the Quakers.

- Their drive came from family inspiration, financial circumstances, or sheer ambition.

- Most were young and hopeful, ready to start afresh.

Not all succeeded in their new world but their stories offer some vivid insights into forces shaping Scottish emigration around the turn of the 18th century.

Read or download ‘Scots Emigrants to East New Jersey: 1682-1702’ here

Read more

Scots emigration to East Jersey

George Pratt Insh, Scottish Colonial Schemes, 1620-1686 (Maclehose, 1922)

Derrick Johnstone, ‘Scots Emigrants to East New Jersey, 1682-1702: Motivations and Outcomes’, unpublished MPhil thesis, University of Glasgow, 2025 Ned C. Landsman, Scotland and Its First American Colony, 1683-1765 (Princeton University Press, 1985)

Cameron Macfarlane, ‘“A Dream of Darien”: Scottish Empire and the Evolution of Early Modern Travel Writing’ (unpublished Doctoral, Durham University, 2018)

Kirsten A. Sandrock, Scottish Colonial Literature: Writing the Atlantic, 1603-1707 (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) Joseph Wagner, ‘Scottish Colonization Before Darien: Opportunities and Opposition in the Union of the Crowns’ (unpublished PhD, University of St Andrews, 2020)

Colonisation of East Jersey

Kristen Block, ‘Cultivating Inner and Outer Plantations: Property, Industry, and Slavery in Early Quaker Migration to the New World’, Early American Studies, 8.3 (2010), pp. 515–48

John E. Pomfret, The Province of East New Jersey, 1609-1702: The Rebellious Proprietary (Princeton University Press, 1962) John E. Pomfret, Colonial New Jersey: A History (Scribner, 1973) William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary Governments (M.R. Dennis, 2nd edition 1875)

George Pratt Insh, Scottish Colonial Schemes, 1620-1686 (Maclehose, 1922)

Derrick Johnstone, ‘Scots Emigrants to East New Jersey, 1682-1702: Motivations and Outcomes’, unpublished MPhil thesis, University of Glasgow, 2025 Ned C. Landsman, Scotland and Its First American Colony, 1683-1765 (Princeton University Press, 1985)

Cameron Macfarlane, ‘“A Dream of Darien”: Scottish Empire and the Evolution of Early Modern Travel Writing’ (unpublished Doctoral, Durham University, 2018)

Kirsten A. Sandrock, Scottish Colonial Literature: Writing the Atlantic, 1603-1707 (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) Joseph Wagner, ‘Scottish Colonization Before Darien: Opportunities and Opposition in the Union of the Crowns’ (unpublished PhD, University of St Andrews, 2020)

Kristen Block, ‘Cultivating Inner and Outer Plantations: Property, Industry, and Slavery in Early Quaker Migration to the New World’, Early American Studies, 8.3 (2010), pp. 515–48

John E. Pomfret, The Province of East New Jersey, 1609-1702: The Rebellious Proprietary (Princeton University Press, 1962) John E. Pomfret, Colonial New Jersey: A History (Scribner, 1973) William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary Governments (M.R. Dennis, 2nd edition 1875)